The Cavafy Family

The poet Constantine Cavafy was born in Alexandria, Egypt, on April 17, 1863. When the new calendar came into effect, the date changed to April 29, so the latter is customarily cited as the poet’s date of birth. Moreover, it coincides with April 29, 1933, the date of his death, creating a notable coincidence in the registry. During the 19th to mid-20th century, Greek communities flourished in many Egyptian cities; the largest was that of Alexandria. The poet’s parents, Petros Ioannis Cavafy and Charikleia, daughter of Georgakis Fotiadis, had a total of nine children, two of whom died in infancy; one of these was the only girl. Constantine was the ninth and last child. Together with his brother Georgios, who had settled in London, Petros Ioannis Cavafy managed a flourishing trading company, “Cavafy & Co.” which traded wheat and cotton.

The Years in England

The family’s prosperity was to be short-lived. Petros Ioannis’s premature death in 1870 forced Charikleia to leave Alexandria and seek support, for herself and her children, from her husband’s brother in England. The family resided first in Liverpool and afterward in London. We have very little information regarding the poet’s roughly five-year stay in England (1872-1877). Naturally he would have attended school and learned English. In 1877, Charikleia and the children returned to Alexandria; Constantine was enrolled in the Hermes Lyceum of Constantine A. Papazis, where his friends included Mikes Rallis and Stephanos Skylitsis, both of whom died young. Constantine composed one of his first poems (“For Stephanos Skylitsis,” 1886) to commemorate his friend’s death, while he kept a journal of sorts regarding the illness and final days of Mikes Rallis (1889).

Move to Constantinople

1882 saw a military uprising in Egypt; the British navy intervened (the British would rule over Egypt for the following seventy years); Alexandria was bombarded and foreign residents began to abandon the city. Among them was Charikleia, who this time hurried to her family home in Constantinople. The poet described the journey in a journal written in English, which he titled “Constantinopoliad – an epic.” We have only tentative information regarding his three-year stay in Constantinople. During that same year he composed his first verses in both Greek and English, as well as prose in the style of encyclopedia entries. Around the end of 1885 the family returned to Alexandria, and Constantine assumed various jobs. Over the next several years, the family would experience the successive deaths of numerous family members. Cavafy’s brother Petros Ioannis (named after their father) died in 1891, their mother Charikleia in 1899, followed by Georgios (1900), Aristeidis (1902), and Alexandros (1905). His remaining two brothers would die in the 1920s, Paul (1920) and John (1923), leaving Cavafy the last surviving sibling. He had obtained steady employment in 1892, when he was hired by the Third Circle of Irrigation, under British control, where he worked for the next 30 years. From 1908 until the end of his life, he lived alone in the apartment at what was then 10 rue Lepsius 10, in October 1964 renamed rue Sharm el Sheikhj and later renamed rue Cavafy.

Visits to Athens

During his years in Alexandria Cavafy traveled only infrequently, be it to the Egyptian interior (Cairo) or abroad. In 1897 he and his brother John embarked on a two-month journey to Paris and London. In the summer of 1901 he visited Athens for the first time, in the company of his brother Alexander, and kept a journal in English regarding the trip, with detailed accounts of what he saw and whom he met, including Kimon Michaelides, publisher of the journal Panathenaia, the poet Ioannis Polemis, the painter Georgios Roilos, and Gregorios Xenopoulos. Cavafy went on to exchange letters with Xenopoulos, who in 1903 wrote “A poet,” historically significant as the first extensive piece about Cavafy’s work to be published in Athens, in Panathenaia. The poet will again visit the Greek capital in 1905, to visit his brother Alexander, who is being treated in a hospital there and will eventually die later that same year. Cavafy’s last trip to Athens comes in 1932, for reasons of his own health.

The “Legend” of rue Lepsius

Cavafy’s apartment on the second floor of what was then 10 rue Lepsius would, over time, become his customary place for meeting with Alexandrian intellectuals, as well as visitors from Greece. His unusual publication method, certain personal idiosyncrasies, as described by his associates, and his always pointed references to literary figures and books began to create an aura of legend around his person. His public image acquired strong (sometimes distorting) features from the descriptions of the well-known writers and poets, Greek and foreign alike, who visited him, including Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and E. M. Forster. Friends (and sometimes enemies) of his work gave accounts of their conversations with Cavafy either orally or in writing. This sharing of private conversations, as well as excerpts from interviews, also gave rise to the public exchange of mutually negative comments between Cavafy and Kostis Palamas, in an era in which Cavafy’s poetry had begun to threaten Palamas’s omnipotence. The recognition of Cavafy’s importance was often accompanied by parodies (sometimes vicious) that took aim either at the poet himself or at particular poems. After the poet’s death, this trend continued with the parodic mockery of a range of themes, thereby confirming the robust and continual permeation of his lines into everyday life, which continues to this day.

Τhe Cultural and Artistic Environment of Alexandria

During the early decades of the 20th century, alongside the commercial and financial activities of the Greeks of Egypt, significant cultural and artistic movements had developed in both Alexandria and Cairo, most notably the appearance of a range of periodicals and books (even by Athenian writers), satiric yearbooks, and literary journals (Serapion, Grammata, Nea Zoi, Propylaia, Panegyptia, Argo, Foinikas), which in time found distribution throughout the Greek-speaking world. Poems by Cavafy, as well as studies or commentaries on his work, not always positive or well-intentioned, appear in all of these journals. The peculiarities of his poetry, his own personal idiosyncrasies, and his solitary life in the apartment on rue Lepsius without a telephone or electricity comprised an exceptional case that departed from the usual models. Slowly but steadily, his poetry began to spread both in the Egyptian communities and in Greece, acquiring faithful fans, as well as fanatic opponents.

Early Publications

1886 saw Cavafy’s very first publications: the prose piece “Coral from a mythological perspective” in the newspaper Constantinople, and the poem “Bacchic” in the journal Esperos in Leipzig. Both, like many other poems and prose pieces of his early years, were signed Constantinos F. Cavafis, and were later silently repudiated. It has been suggested that the F in his signature stood for a second baptismal name (Fotios), yet the official baptismal register contradicts this view, referring to a single Christian name. Most likely, it was a gesture of respect and honor toward Cavafy’s maternal grandfather, Georgakis Fotiadis. For the remainder of his life, he continued to publish prose and poetry in newspapers, yearbooks, and journals in Alexandria, Leipzig, Constantinople, Cairo, and Athens, though he never published a book. Several of these issues contain responses to the poet regarding the fate of the poems which from time to time he submitted for publication, primarily during the early years of his public presence.

Editorial Practice

We first meet with the idiosyncratic editorial method Cavafy followed throughout the remainder of his life in 1892, when he printed a broadside containing the poem “Κτίσται” (Builders), followed a few years later by the four-page leaflet “Τείχη/My Walls” (bilingual edition, 1897); “Δέησις” (Prayer, 1898); “Τα Δάκρυα των Αδελφών του Φαέθοντος” (The Tears of Phaeton’s Sisters) and “Ο Θάνατος του Αυτοκράτορος Τακίτου” (The Death of Emperor Tacitus), under the joint title “Αρχαίαι Ημέραι” (Ancient Days, 1898); and, lastly, an eight-page leaflet containing the poem “Περιμένοντας τους βαρβάρους” (Waiting for the Barbarians, 1904). In subsequent years, he collected offprints of poems that had appeared in various journals, or had individual poems printed, and formed packets of poems, which scholars retrospectively organized into two categories: two “volumes” (1904 and 1910) and ten “collections,” which contained poems from the years 1910-1932. These quasi-books never circulated commercially; rather, the poet himself sent or gave them to friends and admirers of his work, maintaining fastidious distribution lists. This novel publication method rendered his equally novel poetry elusive and highly sought after. His entire poetic production was later grouped by G. P. Savvidis into four categories: the 154 poems of the “canon,” comprising the poems Cavafy himself put into circulation in his two “volumes” and ten “collections” plus one that was unpublished, but assumed to be ready for printing on his death; the “Repudiated” poems of his early period; the “Hidden” (which Savvidis originally called the “Unpublished”), which were not published in Cavafy’s lifetime; and the “Unfinished,” drafts of poems which the poet never completed.

Nea Techni and Alexandrini Techni

By the 1920s, many young readers in Athens had turned their attention to Cavafy’s poetry; some wrote to ask for collections of his printed poems, or composed commentaries on his work. A first public, official example of the Athenian reception of his work was the rather hodge-podge tribute in the journal Nea Techni (1924), in which a plethora of writers expressed their largely positive opinions about the poet being honored. The tribute was conceived by Marios Vaianos, who corresponded with the poet but never met him, and had of taken it upon himself to act as Cavafy’s agent in Athens, offering important help in facilitating Athenian intellectuals’ communication and contact with the Alexandrian poet. In 1926, the dictatorship of Pangalos awarded the poet the Order of the Phoenix, the only distinction he received during his lifetime. The same year, when most of the important Alexandrian journals had ceased their publication, a new literary and artistic journal, Alexandrini Techni (1926-1932), appeared in Alexandria, which Cavafy not only directed from behind the scenes, but supported financially, in order to promote his work and to refute any negative comments his work might attract. The relevant news columns also note sporadic, isolated translations of his poems into foreign languages.

Translations of his poetry

The earliest English translations of poems by Cavafy were attempted by John Cavafy, the poet’s brother (responsible for the translation in the bilingual edition “Τείχη/My Walls,” 1897), and Georgios Valassopoulo, who translated several poems by Cavafy that were included in E. M. Forster’s books about Alexandria, and also published in T. S. Eliot’s journal The Criterion. During Cavafy’s lifetime, translations of his poems into European languages were rare, appearing most often in foreign-language anthologies of modern Greek poetry. A true translation explosion took place after the second World War and continues to this day, with frequent new editions, even in languages that already boast several prior translations.

The Final Trip to Athens

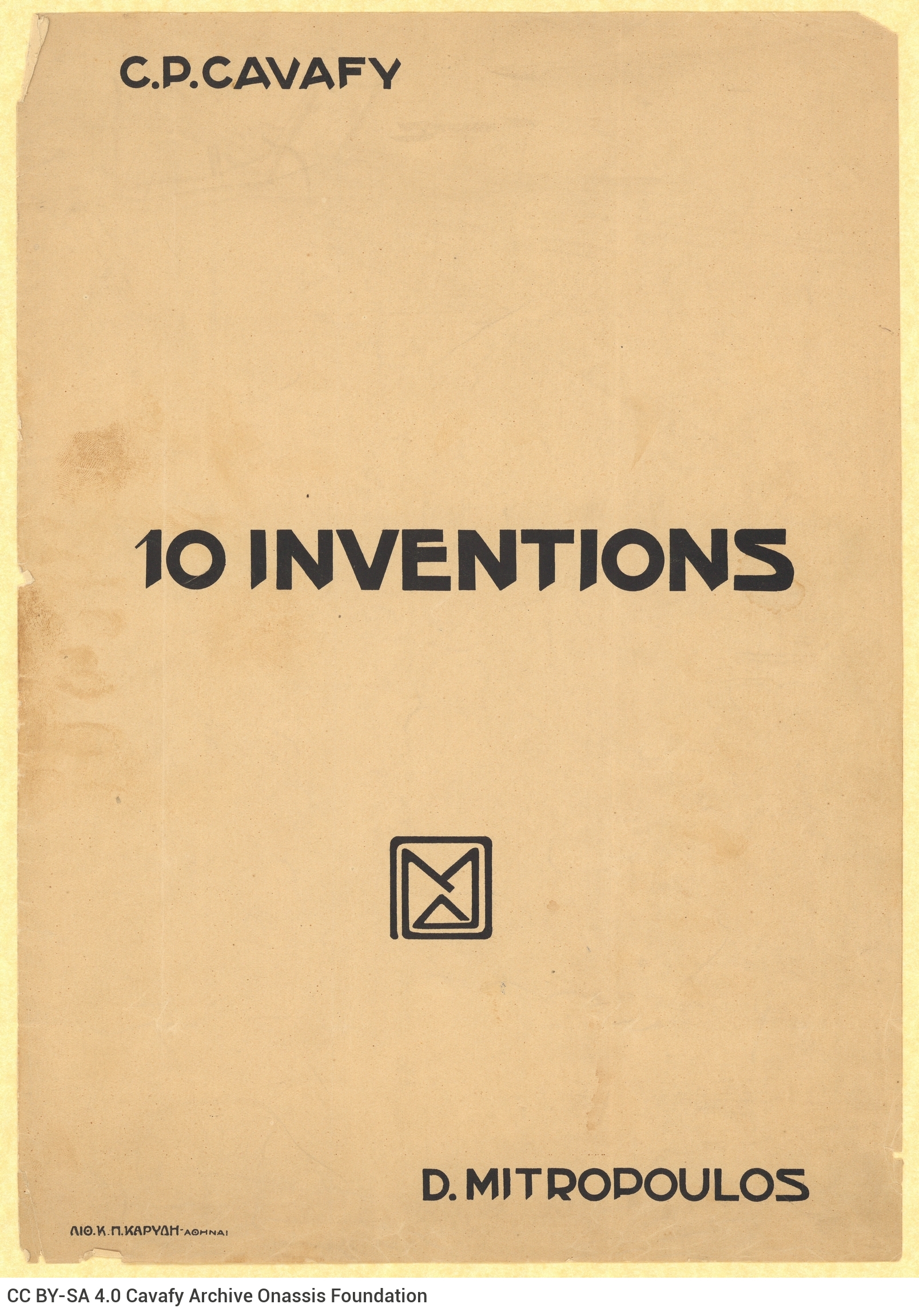

Beginning in the late 1920s the poet was troubled by a discomfort in his throat. “That is what made him quit smoking entirely, become more and more quiet when in company, and be overcome at times by a sudden melancholy,” as Stratis Tsirkas writes. He was diagnosed with throat cancer and encouraged by his doctors to travel to Athens for further treatment; he was accompanied on the journey by his heirs, Alekos and Rica Singopoulo. His presence in the Greek capital met with a great deal of publicity in the Athenian press. He remained for four months (July-October 1932), was treated at the Hellenic Red Cross Hospital, and underwent a tracheotomy, which caused him to permanently lose his ability to speak. His visitors at the hospital communicated with him by way of written notes. On his final trip he met many Athenian writers in person, who recorded their—not always positive—impressions. Before his departure for Alexandria, the couple Kostas and Eleni Ouranis threw a party in his honor, where the composer and maestro Dimitris Mitropoulos performed his work 10 Inventions, a piece for piano based on 10 poems by Cavafy.

Cavafy’s Death and International Recognition

Near the end of 1932, after the poet had returned to Alexandria, a tribute to Cavafy appeared in the Athenian journal

Kyklos. Meanwhile, the state of his health worsened. In April 1933 he was admitted to the Greek Hospital of Alexandria, where he breathed his last on April 29; he was buried in the Cavafy family grave in the Greek cemetery in Shatby. The simple plaque reads:

Constantine P. Cavafy / Poet / Died in Alexandria on April 29, 1933.

According to criticism, Cavafy’s early poetry showed the influence of romanticism; he subsequently passed through periods of Parnassianism and symbolism, to culminate, in the longest and most mature phase of his work, in poetic realism. His ironic language is immediate and powerful, far removed from the obsessions of demoticism; his erotic themes are unapologetic; and the treatment of contemporary events by means of history is perceptible throughout his work. With his lifelong, unfailing devotion to the Art of Poetry, Cavafy spoke of love and death, of the violence and intoxication of power, of political opportunism and the failure of great ideals. Today he is internationally recognized as one of the greatest poets of the 20th century.